[Fictional] The English Roadster

- Feb 19, 2020

- 25 min read

By Art Hanlon

And I know Martin Eden’s gonna be proud of me… Tom Waits

Shiver Me Timbers

When I think of my last year as a kid, it doesn’t surprise me that of all things lost in a boy’s life, I miss my English Roadster most. That glorious bike, a rare hybrid with a redundant braking system: hand brakes fastened to the handlebars plus a backpedaled coaster brake, so beautiful in its simplicity, and so coveted by my coevals in the Madison Street gang that every night I carried it upstairs to my room, crossbar on my shoulder, so it wouldn’t be stolen.

Behold: At night, during a summer rain, you pass through the streets soundless but for the thin, whining hum of the chain and sprocket, the hiss of skinny tires on wet pavement, avoiding the desolation and despair of a Sunday afternoon in the woman-ruled house. You ride to induce the trance that speed offers, taking Myrtle Avenue to Downtown Brooklyn, crossing into the heart of Manhattan, then uptown, heading east over the 59th Street Bridge, weaving through the girders of the Flushing Line El on Queens Boulevard, passing through the acid vapors steaming from the Long Island City factories, bursting through moist lattices of evening neon on the saloon-lined avenues. As you approach the hill, your unreliable wingman, Pete Meagher, on his Raleigh glides out from a side street to follow, and behind Pete, you hear rather than see the blue blur of young Freddy Orlando on his balloon-tire Schwinn as he comes into line, making machine-gun noises with his mouth. You are an Irish airman of the mind, fighting those that you do not hate, boldly plunging down Crematory Hill, the steepest hill in a Queens necropolis, a neighborhood of cemeteries, the gears ratcheting like crazy for the three blocks it takes to reach the high concrete abutment of the abandoned railroad tracks that seals off the last dead-end street.

Here’s your trick—your rite of passage: The intersection of Crematory Hill Drive and Fresh Pond Road has neither traffic light nor stop sign, and you seem to toy with mortality by refusing to check for cross traffic as you lead Pete and Freddy through the intersection at top speed. You call yourselves Three of a Kind. Nobody else has the nerve to follow. Your estranged grandfather’s redbrick bar and grill squats on the corner of that intersection, old Jack Houlihan’s place, the red neon Old Bushmills sign in the window, and every time you wheel by, you sit up straight in the saddle and use the warped window of your grandfather’s bar to see Fresh Pond Road in both directions. You slow down or speed up to get all safely through the intersection without telling Pete or Freddy how you do it. You defiantly stretch your arms out, as you pass that old man’s saloon, your hands swiveling at the wrists like ailerons, and wonder what would happen if you burst through the front door and skid hard to a sudden stop, leaving a double streak of black rubber arced like the trail of a sidewinder on the wooden floor in front of the nineteenth century mahogany bar, the rail polished by a hundred and fifty years of resting Irish forearms, and announced yourself to your namesake grandfather, old Jack Houlihan, with his cauliflower ears and glass eye, the old, bare-knuckle street fighter who never did learn how to transcend the street and fight like an athlete in the ring: Hi, here’s my forged birth certificate—give me a beer.

I’m Going to Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter. I’m sure it all really meant something—my last summer in Brooklyn—the smell of ozone in the air just before a storm, the rumble of over-the-horizon thunder on a clear, blue-sky day, sun-shower raindrops sizzling on baked asphalt, Billy Williams singing a Fats Waller song on the box, and the smell of pizza just out of the oven—New York-style pizza, thin crust, but thick with tomato sauce and bubbling layers of cheese too hot to eat right away, but releasing heat and aroma into the faces of all of us sitting in a booth of the Napoli Pizza Parlor. It was at the Napoli that I met Annette, the daughter of Sal, of Sal’s Athletic Club, or, as known to us in Madison Park as Sal’s Pool Hall directly across the street from the Napoli. My English Roadster brought me to her as if it had a mind of its own.

One sultry dog day in late August, tired of the tough Madison Park street gang, the Three of a Kind decided to try out the Napoli as a new headquarters. It was under the Fresh Pond Road el station, only two blocks down from Madison Park. Pete and Freddy got bored soon enough and rode their bikes back to the park. Not me. For some reason—maybe it was my solitary bike and my heedless manner—Annette, with her little sister in tow, singled me out that first evening to push me into her private booth and tell me the latest news about her boyfriend, Tony, Freddy Orlando’s older brother, him being the reason, she said without specific elaboration, that she stayed away from Madison Park. The tractive charm in the way Annette told her story piqued my curiosity, and I decided not to follow Pete and Freddy back to Madison Park. I stayed at the Napolito hear more.

One night, I persuaded Pete to return to the Napoli with me, but he fidgeted with impatience as Annette told me all about her unsatisfactory boyfriend. Tony was one of Pete’s idols. Tony was such a powerful neighborhood presence that Pete wasn’t the only boy who tried to imitate his nastily insouciant manner. Tony owned the signature physical presence of the decade: the greasy pompadour, the bony frame sliding around inside his motorcycle jacket, the way his blue jeans rolled up at the ankles hung on his hips, the way he slung his thumbs in his back pockets and hung his head just so, looking up at the girls from under the blond übermensch curls framing his forehead. He was so perfect in his self-invention, he could have had his slouching posture patented if James Dean hadn’t beaten him to it. But Annette resented the way he made up rules for her, the way he smoked as he paced in her living room listening to music and ignoring her as she solo-danced in front of the oval mirror over the fake fireplace, the way he combed his cowlicked hair, the way her father, Sal, liked Tony because he was half Italian and went to Mass every Sunday. In fact, Tony was so ostentatiously devout, he made the sign of the cross every time he walked past a church. Now that was Old World stuff. “He must have some mama,” Annette’s father would say. And Annette would answer, “But he doesn’t pay any attention to me, Papa.”

“He has plans, sweetie,” her father finally said one day, “stuff on his mind, still waters.”

Annette, exasperated, put an end to the discussion by telling her father that every time Tony took out his switchblade and clicked it open and closed, as if hypnotized by the graceful mechanics springing the blade, she took it as a sign that maybe Tony had mechanical aptitude and that he would get a job someday. But no, Annette said, she knew the real Tony, and he was very dangerous; a selfish, preening, half German, half Sicilian thug, a blond Italian leading a gang of younger neighborhood boys, while aspiring to join the real gangs, the Chaplains, say, or the Halsey Bops. If Annette spoke to another boy, that boy’s life wouldn’t be worth a dime. Or so she said. Pete scoffed with an involuntary snort, which embarrassed him, and he rushed out, quitting the Napoli for good.

I caught up with Pete under the Fresh Pond Road El just as a train was pulling into the station. He tugged me farther under the elevated tracks, back by the old abandoned trolley barn. He had to shout over the train grinding on the tracks above. “Tony will kill you.” Pete, the rolled legs of his blue jeans hanging over his sneakers, walked away through the shower of sparks falling from the third rail as the train pulled out of the station above. Annette was three years older than me and long out of high school; maybe that’s why I was drawn to her in a way I was not by the other girls in the park. Pete’s parting shot was to tell me how Tony told everyone in the Madison Street gang that Annette had been around the block a time or two. For me, this only added to her allure, as she seemed incomparably experienced and streetwise, although I pretended to be her equal when we were together. I decided to let Pete go.

I felt powerful, independent. I was welcoming risk into my life—the beginning of a bad habit—like winning big in a casino the very first time you threw the dice. The very next day, I compounded the risk by commencing casual afternoon walk-throughs of Sal’s Pool Hall, until one day I saw Tony casually surveying his options on the pool table, squinting from the smoke of the cigarette drooping from his lips, a package of Lucky Strikes rolled up in the short sleeve of his T-shirt. I noted the way he held his pool cue under his arm like a jousting lance, its blue tip resting on the rail of the pool table, and wondered how quickly he could turn it into a weapon. I was beneath his notice, which suited me fine because the only reason I entered Sal’s was to learn what kind of a world Annette had grown up in. I never saw her in the pool hall, although I was certainly aware of the baleful and suspicious eye of the actual Sal, her father, who was perched on a stool behind his caged desk as he followed my progress through the bustling, nicotine-infused cloud chamber of the main floor, the green felt tables lined up from the front door, past the Coke machine, the cigarette machine, and out the back-alley door. He stared at me as if he knew I wasn’t just another non-paying, pool hall loiterer. There was never a sign of Annette in the pool room. And yet she never failed to show up right after I chained the English Roadster to the streetlight pole in front of the Napoli.

The narrow front room of the Napoli had a counter in front of the ovens on one side and a bench with stools along the opposite wall but opened into a larger and more spacious dining room in back. The red carpet was dark and wine-stained; the walls had the usual prints of old Naples, the coffin-shaped gondolas poling in the Venice canals. One night, Annette, wearing an A-line skirt and a man’s black sports coat over an untucked white shirt, rose from our booth, put a dime in the jukebox, selected “Love Me Tender,” slicked her dark hair behind her ears, and began her special dance in the center of the room. Each table had a candle, and we shut off the lights and watched Annette dance in the candlelight. She danced Tony-Combing-His-Hair, a toothpick in the corner of her mouth, her face a caricature of sullenness, mimicking the false casting of Tony’s hands as he shot his cuffs, his girlish fingers daintily holding the imaginary comb. The tables with red-checkered tablecloths had been pushed back, and Annette had plenty of room to dance. She began with an Elvis Presley sneer, which she slowly transformed into an open-mouthed, eye-rolling tremor of pure narcissistic ecstasy as she pulled the imaginary comb through her hair in deep, wistfully sensuous sweeps all the while swaying her hips to the beat.

It was that sudden, instantaneous, and I was in over my head—her small feet, expressive hands always in motion, her wide smile, her cheekbones, and her black, black hair, wetted down beforehand so she could pull it back behind her ears and straight down to her shoulders. Where did her kind of grace come from, so mesmerizing, so strange, and so ineffably human and alien at the same time? It had to come from somewhere beyond the earthly plane, maybe from the spirit belt that some Native American tribes believe circles the planet, or from underground, siphoned off from the magma force that shaped the earth until it found and possessed her in an entirely different way than how that force seemed to reach through her to possess me.

I never really knew if she felt the same way, but when we strolled down Catalpa Avenue toward the baseball field at the Farmer’s Oval, she spoke as if something had been decided. “If Tony finds us together, will you protect me, Jack?”

“Sure,” I said, wondering how I would do if put up against the rough star of the neighborhood. “But what is it with Tony? He likes you, doesn’t he?”

“He loves me.” I could sense Annette watching me closely as we walked in the shadows. “More than anything,” she added. She veered and did a little pirouette around a bus stop sign and came back to me.

“I wonder if you’re too young for me, Jackie—that bike, that goofy hair, when are you going to get a haircut?”

“Never!”

“Oh, you are such a boy!”

When we got to the Oval, the gate was padlocked, but Annette hit the fence running and was over in two bounds. She didn’t care what I could see, her bare legs, her panties as she went over the top of the fence, the folds of her skirt bunched in one hand. I hit the fence a few seconds behind her. I was going to keep up or die. She was running across the outfield before I hit the ground, making me chase her to the highest row of the bleachers where she stopped and waited, leaning over the wall. We stood side by side on the top bench with our elbows across the parapet looking over the neighborhood, all quiet except for the sound of our breathing and the crickets in the tall grass by the railroad tracks on the other side of a gleaming, moonlit cyclone fence. The waxing half-moon floated high over the silhouetted buildings and the smokestacks of the mills, and its light shone on Annette’s face, brightening her cheekbones, her eyes in shadow. I was so captivated by love for the first time in my life, and everything about her was a glorious mystery.

“God, you can run fast,” I said, panting in sharp bronchial pain.

“I know. For a girl, right?” She raised her arms in a V, her little fists waving in the air. “Girls’ cross-country track at Grover Cleveland High.”

Somehow, I found the courage to kiss her. I’d been thinking about it all night, and she didn’t push me away, much to my relief, but accepted my kiss with an at lastsigh, as if it had been her idea all along and I had finally caught on. I had my arms around her, enthralled by the warmth of her body moving against mine, thrilled that she thought I was worth her attention. Her every move was a signature of inspired creation. Now as we shyly and sweetly made out for the first time, kissing each other and touching each other so tenderly—it was as if we were handling ripe peaches and were afraid of leaving bruise marks.

For the rest of the summer, she let me dance with her in the Napoli dining room, creative, free-form dancing, wild, until one night toward the end of August, we had our last dance together. She had her hair in braids hanging down past her shoulders, not really very fashionable, and wore a sleeveless blouse and her favorite, dark blue, A-line skirt. We acted out an entire movie. Scene one: I beat on the table, “You’re tearing me apart!” Annette started her famous fake crying, so realistic with inhaled shrieks and hiccups, and cried, “I thought he’d rub off my lips!” And the way she said it, holding her sister’s patent leather box purse under her chin with both hands, her lower lip pushed out in petulance, cracked everyone up before she even finished the line. She got more laughs than I did, but I didn’t mind, because the last scene was mine: I dramatically fell to my knees in the space between the tables, tortured my face with that famous squint and cried, “No! No! I’ve got the bullets! Loooook!” And I’d draw out the “look” until I saw tears in the eyes of one or two of the girls. Afterward, she sent her sister home and we walked. She insisted that we keep to the side streets, taking long, bouncing strides, the walking style of the day, keeping to the shadows because she was afraid Tony would find us—he was already suspicious—he had a gun—he was unpredictable—we needed to be careful—“Eek! Is that him now?” No. Only the indifferent headlights of passing cars, spotlights lighting up her dramatization of stealth. She was testing me, I suspected, to see if I would release her hand at the moment of truth—her own little fight or flight loyalty test.

At the Oval, in the high benches, we started kissing ferociously, without preamble, the teenage couple of the times. Our pizza-parlor dancing had transformed us into the self-appointed archetypes of our tribe, making out on the steps of a California Movie Temple of the Stars—the anointed stand-ins for everybody else. Lost in our passion, a single kiss lasted a long time, and there were many of them until she opened her blouse with a surprisingly hopeful expression. “Can I touch them?” My voice quavered. She nodded Yes!, her smile turning more confident and eager as she unhooked her bra and lifted her breasts with spreading fingers, tilting her head coquettishly, mocking my desire, tauntingly inviting, as if to say, “Come and meet the Minotaur.” I weighed her left breast with my cupped hand, squeezing it gently, so soft and bouncy. She brought her hand up and squeezed my fingers hard around her nipple. “Doesn’t that hurt?” I started to pull my hand away. “Yes,” she said breathlessly, catching and returning my hand to her breast. “But I like it.”

We ran to the outfield, sprawled on the grass, and after a rushed and sweaty entanglement, Annette reached under her skirt, took down her panties, slipped under my skinny body and got me inside of her. As I was drawn inside of her encompassing warmth, I started to suspect that maybe, just maybe, I was irresistible. I had stolen her away from Tony! I lifted one of her braids, placed the end of it on top of her head, which made her smile, tasting salt as I kissed her neck behind her ear, so fragrant with the estral ambrosia of passion, my jeans looped around my ankles, and then, just as I began the gathering rush to the center of an exploding star, she pushed me off with a violent shove and struggled to get up. “My boyfriend! It’s Tony! My boyfriend!” The blood was not in my head where it belonged, and when I scrambled to my feet, trying to yank my pants up, I had a dizzy spell, tripped over my own twisted clothes and hit the ground hard. I was ready to fight, but there was no actual Tony in sight, only the bleak emptiness of the outfield.

For a short time, we rested side by side, breathing like two lost sparrows, the silence only broken by the occasional chuckle from Annette. For the first time, I noticed the paper, gum wrappers, and crumbled cigarette packages caught in the unmowed grass of the outfield. A half-moon tipped sadly over the rooftops, a hollow clay bowl, not quite bright, chipped and stained, spilling stars like liar’s dice across the gauzy summer sky.

“C’mon, Jackson, it was only a joke,” she said.

I sat up, but I didn’t look at her. I couldn’t bear to see the expression on her face, or for her to see mine. A truck boomed on Fresh Pond Road, a train on the Myrtle Avenue line squealed. She was right; I was just a boy. Then, half to herself, “I don’t want to get in trouble.” Far away in some other concrete canyon, a police car siren bounced whooping echoes through the streets. The street world slipped back into place as that Brooklyn serenade howled through the avenues. She put her hand on my neck and slid it down to massage the part of my shoulder that had broken my fall. “Ah, poor Jackie,” she said. She pushed on my shoulders to make me lie back down. And with her at first taking the lead in what might have been intended as a “mercy make-out session,” we slowly got carried away until we fell into a feverish rush, and there was no longer any question of restraints or jokes, or who was leading whom, or mercy or cruelty, or anything except the understanding that we were no longer making out; we were making love.

Later back in a window seat at Napoli’s, Annette, one hand on the table, the other making a fist propped under her chin, gazed at her father’s place across the street. She stayed that way for a long time, humming a song I didn’t recognize, keeping time with the visual metronome of the blinking neon over the front entrance to Sal’s Pool Hall where Tony was presumably knocking balls around with a stick. When I reached for her hand, she pulled away, looking at me with large, brown, offended eyes. “My boyfriend is going to be very angry when he finds out what you made me do, you horrible boy.” For a minute I didn’t know if she was kidding or not: my first lesson in gender politics.

-----------

“So, you must have heard about Freddy.”

I was repairing a flat tire on my bicycle when I noticed Pete standing in our patio, fists clenched, his Irish lower lip stuck out in some terribly offended dignity. He must have climbed the iron gate and approached through the alley without notice, sidling along the brick wall of the neighboring apartment house, his diddy-bop movements so contrived I thought he was playing a role.

“No. What happened?”

“No? What happened? He’s dead, you son of a bitch.”

The bicycle tire spun under the palm of my hand. I tried to read Pete’s face to see the joke, but all I saw was red anger, a vein in his scarlet temple throbbing. “We were riding on Crematory Hill, and he wanted to go down the hill first. When he got to Fresh Pond, he didn’t slow down, or look, or anything!”

Pete grabbed the spinning wheel and threw my bike against the brick wall. I snatched him up by the shirt, pushing him up against the wall, stepping clear of the wheel spokes spinning on the ground, trying to get a grasp on the situation. Freddy dead? Pete twisted and I let him push me away. Maybe I deserved this, but I hit him in the arm just below his shoulder preemptively with the knuckles of my fist without anger. We’d never fought seriously before. Pete was off-balance and staggered back a few steps. I raised my fist again, but instead of punching him, I pushed him hard toward the gate. Inside the house I heard my aunt, drawn to the commotion in the yard, crossing the dining room to the pantry and the back door. Pete turned and started for the street, mumbling as he made his way past the cellar door, half-tripping over his own feet. He halted at the iron gate and holding it open, turned to face me again. “Only this time a truck was turning from Metropolitan Avenue. It’s your fault! Why didn’t you just show him the trick?” Pete backed through the gate, slamming it closed, and with one last hard glance through the tall spiked bars between us, he turned and walked fast across the street to his house without looking back.

What I never told them: Pete didn’t know how I did it, but he knew there was a trick. My aunt came out of the house.

“I thought I heard Petey out here?” she said, looking down the alley.

“Does he want to stay for lunch?”

“He had to go.”

That night at Madison Park, the girls, usually a chorus of parakeets, sat in a row on the park bench, uncharacteristically quiet and reserved, brushing their hair, chewing gum, passing their mirrors around. All but one tried to ignore me as I made for the cyclone fence, their heads nodding together as they shot furtive sidelong glances full of reproach in my direction before gazing expectantly over at Sal’s Pool Hall. The one pony-tailed girl who stared steadily as I went by whispered in a voice like a nail file rasp, “You’re gonna get yours.” Someone else said, “Here they come.”

I looked over at Sal’s to see four boys leave the pool hall, cross the street, and walk into the park. Pete was one of them. Two others I had seen around, but didn’t know, and then last, the tallest of the four was Freddy’s older brother, Tony Orlando, Annette’s so-called boyfriend. It was plain to see that Tony was Pete’s new best friend.

Pete trailed slightly behind, but he walked in step and kept up with Tony as he moved past his two friends and took the lead. Pete gestured at me with his chin as he approached, his eyes burning into mine. I lip-read his “that’s him” as he spoke into Tony’s ear. I had to be pointed out? Tony hastened his pace, bouncing on the balls of his feet, his shoulders dipping with exaggerated rhythm, imitating the tough blacks from Bedford-Stuyvesant, his belt buckle shining like the headlight of an oncoming train. He didn’t hesitate, didn’t waste words, but just increased his pace as he drew closer. His first punch hit me high on the skull and glanced off, not doing much damage. Tony was fast but not that fast. I saw it coming in time to get my arm up. Then I got it dead behind the knees with the heel of someone’s stomping boot, and I went down. I instinctively curled and covered up until I became aware of Tony’s head above mine hissing imprecations that pierced the confusion of fists and boots. His motorcycle jacket reeked of stale cigarette smoke, his breath of garlic and hard liquor. I caught a glimpse of his eyes, surprisingly vulnerable, a hint of hurt in the deep yellow of his anger and something else even more unexpected: wonderor something very much like it. Pete had halted in his approach at the last second to let the others pass, mouth-breathing in great gulps as he stared. He didn’t make a move, but only watched, ringside, as it were, his clenched fists twitching in tight, spastic jabs as each boot swung home. When we were little, Pete was my best friend.

The girls didn’t run, or scream, or cry, but simply witnessed, eyes glittering with the sensual excitement that triggers the kind of male behavior they will eventually protest. Finally, I looked up at the circling gang of four and registered a fifth face gazing down. It took me a few seconds, but through the slits of my swollen eyes, I saw that it was Freddy and he was propped up on crutches—his ankle in a cast. “Hi, Jackie,” he said. He was grinning.

In the morning, I sat up in bed after lying awake for most of the night. The room smelled like rancid Thunderbird, which I had puked up after staggering through the door long after midnight, my knuckles scraped, an egg of pure bone pushing up from the ridge over my eye. I didn’t know if I had won anything, but I had come up swinging, upsetting their schooling with an inspired resistance full of virtuous resentment and a satisfying anger so deep and so unspecific that I had to wonder where it all came from: the right stuff. Overnight, a weather front had passed through, dragging in a misty, drizzling, New York grayness, cold and relentless; blue window in the rain. I lay awake for hours, trying to fight off my presentiments and organize my thoughts: my family, my high school, the rumors comprising a family history, and then there was my religion, such as it was—grafted irrevocably now to the poetry I’d been reading, a strange hybrid, the ancient music. And then I knew what I was going to do with my forged birth certificate.

-----------

The weekend before I left for Parris Island, I saw Annette amid the post-Christmas throng in front of Woolworth’s on Myrtle Avenue. It was a cold morning with a scattering of snow in the air. For the first time, I was able to talk to her as if I were her own age, as if my secret aspirations had made me wise—as if imagining life was equal to experiencing life. I was shocked to see that her black hair had been cut short so that her formerly smooth locks were bobbed in a straight line even with the bottom of her ears, the sharply cut, brushlike ends poking out of the blue, paisley kerchief tied Russian babushkastyle under her chin. She smiled with genuine happiness when she saw me. I tried to take the sight of her in, to absorb and impress her image on my mind’s eye, wanting to prolong the conversation. “You cut your hair.” It was all I could think of to say.

Annette raised her hand and pushed at her short bangs. “Tony’s idea.” A quick look of irritation crossed her face. “Do I look like a boy?”

“Never.”

Small, dry snowflakes were caught in her brand-new bangs and her eyelashes. Her face changed when I told her I was leaving for Parris Island in a few days. She asked me if I was quitting school, and I said I already had and that I planned to get my high school diploma through correspondence school. “The recruiter said people do it all the time.” She shook her head and put her hand up to my face. “What is it?” I asked. She slid her hand to the back of my neck, pulled herself up and kissed me on the lips. It was quick enough that I didn’t have time to kiss her back. “I thought you were smart,” was all she said.

I watched her as she walked briskly away down Myrtle Avenue, the store windows reflecting dull January light, hoping she would at least look back. When she didn’t turn around, I almost ranafter her, all my defenses collapsed, but I stopped short when I realized that her kiss was not just for luck; it was a good-bye kiss to one abandoned, as if she understood, well before I ever figured it out, the enormous profundity of the future that I was truly leaving behind.

--------

On the morning I woke up in my own bed for the last time, I listened to the familiar sounds of the house: my aunt, home from her night shift for the Transit Authority, the sound of dishes being put on the table, the radio talking about a grasshopper plague in Colorado, Uncle Frank padding up from the basement apartment for breakfast in his bathrobe and slippers, opening the Timesto the crossword puzzle. Mom had already left for work; my sister was in the bathroom, getting ready for school. I could smell coffee brewing and hear water running through the pipes and the muffled conversation of my aunt and Uncle Frank. There would be crumb cake on the table from the German bakery on Forest Avenue. I dressed and slipped out of the house with my English Roadster.

I rode past Pete’s house, where a cardboard box filled with brown Rheingold empties leaned in the soiled, ice-crusted snow on the porch stairs. Good-bye, Pete. I rode by the apartment house where Tony and Freddy lived, metal trash barrels in the alley waiting for collection. I turned on Fresh Pond Road and pedaled my way slowly in the direction of Myrtle Avenue. I passed Lotner’s Grocery, the Chinese laundry, the diners under the elevated line, the candy stores with racks of newspapers, the ice cream parlor, Napoli’s, the housewives pulling their two-wheeled shopping baskets behind them, the blind vendor and his third-eye German shepherd selling stale pretzels at the entrance to the Fresh Pond Road el station. I cut through throngs of breathless commuters passing through the steam rising from the manhole covers, rushing up the ramp to the station platform, carrying briefcases, paperbacks, and newspapers. I swore I would never be one of them. The Manhattan-bound train pulled into the station, sparks showering down in bright streamers. The little, Catholic schoolchildren in their uniforms were walking to the same elementary school I had attended, exhaling puffs of fog, the little girls in their long wool coats, red and blue, wearing pigtails and holding their books with their arms crossed in front, the boys in Mackinaws and galoshes with their cowlicks and leather book bags.

Farmer’s Oval was empty except for the carefree dropouts playing basketball. They had stripped to their T-shirts although it was January and shouted mild insults at each other as they wove around the court, dribbling and blocking. I pedaled to the baseball diamond and sat in the bleachers, staring at the cold, empty outfield, mounds of dirty snow and ice obscuring the baselines. Only last summer Annette and I had lain on our sides in the outfield grass, leaning on our forearms, heads propped on fists, forming the only equilateral triangles I found of interest.

About noon, near my grandfather’s saloon, I pushed my bike to the top of Crematory Hill. I sat for a while, leg hooked over the crossbar, gazing over the Brooklyn rooftops, the brown- and redbrick apartment houses with old, ashy snow on the windowsills, the church steeples, the smokestacks of the mills, the neon signs of the saloons lining Fresh Pond Road all the way to the Metropolitan Avenue elevated train terminal, set so ironically amid the tombstones of Mt. Olivet Cemetery. For the first time that day, I felt the January cold down to my bones, and I shivered, gathering my thin jacket closer. Something within me had changed—it was sudden and visceral, and my pulse quickened as I sensed I had finally lost what I had been trying to lose for so long. The girl in the park had said, “You’re gonna get yours.” I wondered what Freddy felt when he hurled himself into the traffic of Fresh Pond Road—romantically gambling with the cosmos. For a few stunned seconds, I inhabited my future self, returning here to the top of this hill so many days ahead I couldn’t even imagine when it would be, or what the city would look like, and I felt the first bleak stab of a deep, abiding loneliness.

Then, with an anger I did not yet understand, I tipped my bike over the edge and with one push on the pedals, I started down the hill as fast as I could possibly go. I picked up almost more speed than I could handle right away, and full of dead purpose, I struggled to maintain control until some primal, deterring barrier gave way, and I relinquished even that last hold-out margin of self-preserving care. I was having the perfect ride—my arms outstretched; the clear, cutting January wind drawing ice-cold tears from my eyes; the leafless branches of the trees clawing the sky above; the brittle, refrozen snow crackling under the tires. I kept to the center of the street, steadfastly refusing to even glance at the window of my grandfather’s gin mill, determined to avoid both the stacked deck and any last-second bargaining with the cognizant sky. I wanted this to be an authenticride, challenging the randomness of things-as-they-are, and I went through the intersection blind at fifty per, I’m sure of it. I don’t know what kind of crazy luck it was, if it was luck, but, rolling way too fast to make any sudden adjustments in speed or direction, I crossed the intersection just as a red gasoline tanker truck and a ’56 Ford met and passed in their respective lanes at the very center of the crossroads. I passed between them with milliseconds to spare, horns blaring in wild, sliding Doppler shifts. The windows in the brick houses on both sides of the street, their shades drawn, reflected only cold, enameled sky, passing like white Magic Marker gesture drawings in the corners of my eyes gauzy with wind-drawn tears. I coasted for two more blocks, standing on the pedals, my heart pounding, rolling all the way to the concrete wall of the dead-end railroad abutment where I skidded to a halt. Then, breathing hard, on the verge of hyperventilating, and trembling uncontrollably at what I had just done, I watched, amazed, as a string of boxcars rolled by on the railroad tracks above the embankment on the spur of the New York Central Queens-Maspeth subdivision that had supposedly been abandoned, the boxcars swaying, the Seaboard Coast Line, B&O, Norfolk Southern Railroad, the Frisco (Ship it on the Frisco!); New York, New Haven & Hartford in cursive, a baggage and mail car with an embossed double E painted red over the sliding door, the Erie Lackawanna; Rio Grande, the Action Road. I listened to the beat of the wheels clicking on the rails and ties, the rhythmic iambs on the main line yielding to double dactyls when the boxcars crossed the switch. The yard switcher engine, huge and black, smelling of heat and diesel fuel, looming from a tunnel braced with massive, concrete-retaining walls supporting a gantry of green, yellow, and red signal lights and semaphores, came to a grinding halt, tooted twice, and reversed direction, boxcars all down the line booming as the diesel engines powered up to overcome tons of inertia. The brakeman, in red shirt and coveralls, sat in the window of the switcher as it went by, and I waved. He shifted his weight and waved back with his lantern, and we kept waving until the swinging arc of his lantern disappeared back into the tunnel. Then it was quiet, and I was alone with the slowly ebbing excitement of my ride down Crematory Hill, and I guess that’s when I figured nothing cold—certainly nothing as cold as death—could ever touch me. I left for boot camp in deep winter not long after the earth quietly slipped on its axis, and the English Roadster, chained to one of earth's many fences, began the long trip back to glory in a boy's summer sun alone.

Art Hanlon was born in Brooklyn, New York. After serving in the Marine Corps, he attended the University of California at Berkeley, taking a bachelor’s degree in American history and English, and a master’s degree in journalism. He worked as a newspaper reporter, a country blues musician, a theater set carpenter, a technical writer, and a book editor before returning to the University of California Riverside Palm Desert for an MFA in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts. He is currently an associate poetry editor for Narrative Magazine. His song, Spokane, won first prize in the 2005 Tumbleweed Music Festival in Richland, Washington. His essays and fiction have appeared in Surfing Illustrated, Art Access, Narrative Magazine, and Coachella Review. His essay The Brilliant Present was included in the Special Mention section of the 2019 Pushcart Prize Anthology.

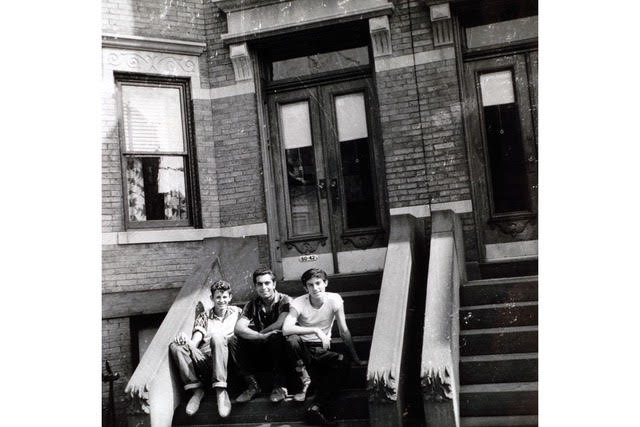

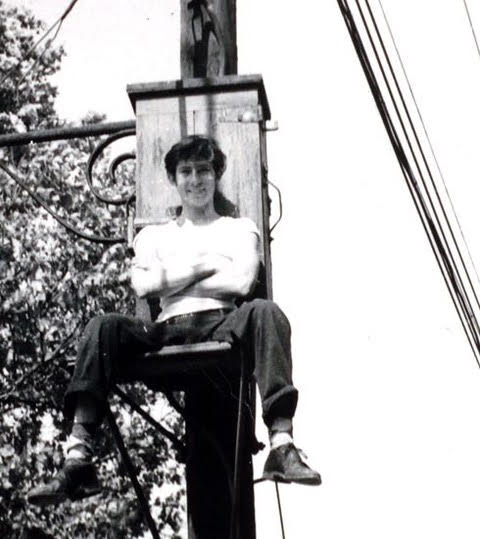

Queens, NY Circa 1958 ~ Photos by Art Hanlon

![[Interview] Barbara DeMarco-Barret Pool Fishing](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/52c352_643c6850bc174b1683e59615d3b9ba81~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_980,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/52c352_643c6850bc174b1683e59615d3b9ba81~mv2.jpg)

![[Book Review] Outliving Michael by Steven Reigns](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/52c352_e4733806c2b541a1ad630a04986aeb76~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_500,h_500,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/52c352_e4733806c2b541a1ad630a04986aeb76~mv2.jpg)

![[Non-fiction] Surfers Just Know Other Surfersby Scarlett Davis](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/52c352_7b5a11f65056417a8d2d770820dde8aa~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_626,h_417,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/52c352_7b5a11f65056417a8d2d770820dde8aa~mv2.jpg)

Comments